Miscellany — Spring 2013

The marginalized Alexander Pope

By Dr. Robert V. McNamee

Spring 2013 marks two significant anniversaries for Alexander Pope, perhaps the most representative and alien English poet of the 18th century. Pope is memorialized both for the 325th anniversary of his birth, on 21 May 1688, and for the 300th anniversary of two significant literary acts: one a publication, the other a proposal to publish.

On the 7 March 1713, Pope published one of his most important poems. Windsor Forest was published the same month as the signing of the multi-stage Treaty of Utrecht, with which, in part, the poem deals: “Hail, sacred Peace! hail long-expected days” (Windsor Forest, line 353). The redistribution of territories determined by that treaty created various, continuing friction points between Protestant Britain and its Catholic adversaries: France ceded vast North American territories to Great Britain leaving French Canada surrounded by English lands, while Spain ceded Gibraltar to Britain and acquired the Falkland islands (Islas Malvinas). It was a period of global, territorial conflicts, but passions were inflamed by the Protestant/Catholic schism.

Later that same year, Pope made public, and sought subscriptions for, a proposal for the first major English translation of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey since that of Shakespeare’s contemporary George Chapman (1559–1634). Pope’s Homeric effort became one of the major cultural accomplishments of the period: in a letter of 4 October 1726, Voltaire praised Pope’s fingers, “which have dressed Homer so becomingly in an english coat”. (Electronic Enlightenment letter ID: voltfrEE0010001c1c)

As a man, Pope himself has at least two claims on our attention, though his anniversary will undoubtedly rank lower in public attention than would that of many other poets of these Isles. A Google search on English poets by forename and surname lets us plot a rough graph of Internet popularity:

Graph of search results for English poets

However, there are other digital measures of a poet’s popularity. Pope’s epigrammatic style and his rhyming couplets, which suffered critically at the hands of the Romantics and later generations, now proves to be remarkably popular among the choruses of Twitter, where there are a number of “Pope” persona:

@MrAlexanderPope on twitter

— and endless Pope Tweets, quoting (or misquoting) lines from his verse. Pope’s epigrammatic couplets were crafted to place a succinct thought within a limited number of words:

Twitter search for ‘Alexander Pope’

One of the things that continues to intrigue about Pope, is his extraordinary confidence and ability to focus on his vision of what he should do and be in life. Two years before the date marked by this anniversary, Pope published one of his two great “epigrammatic essays” — An Essay on Criticism (first published anonymously, 15 May 1711). Pope was only 23, and the work does more than mark him out as a singular and singularly memorable essayist on the human condition. It presents us with the noteworthy instance of a young man, still at the beginning of his literary career, publicly admonishing and correcting the established critical community. It reminds me of the equally confident, if often less accessible, manifestoes of the Modernist movement.

For Pope was no social or cultural insider, but what might be thought of as a “corporeal and incorporeal outsider”. Pope was twice marginalized in his world. Marginalized once for his beliefs — as a Catholic, then barred from teaching, attending university, voting or holding public office on pain of imprisonment. The anti-Catholic sentiment was aggravated by the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), which led to a statute preventing Catholics from living within 10 miles (16 km) of either London or Westminster.

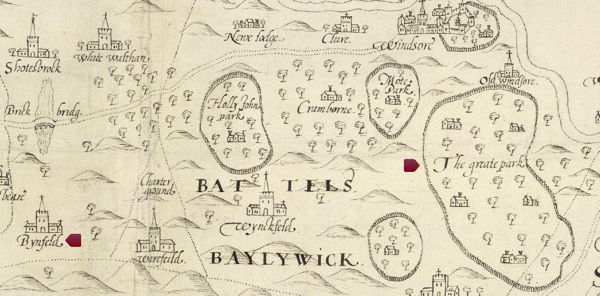

These constraints would have pinched especially hard on the ambitions of Pope’s essentially middleclass family. They were prosperous enough, however, to be able to escape to the country, moving to a small estate in Binfield (or Bynfield), Berkshire, when Alexander was twelve. Binfield was only a dozen kilometres west of Great Windsor Park, though remains of the ancient royal hunting grounds of Windsor Forest undoubtedly “crown’d with tufted trees” (Windsor Forest, line 27) various plots between the two. On the verges of these forests, you could pretend to be anyone, and one’s beliefs could be recast in the poetic imagery of patriotism and Classical analogy we find in Windsor Forest.

Estates at Windsor, Berkshire — British Library, “The unveiling of Britain” © The British Library Board, Royal Ms. 18.D.III, f.32

Pope could never escape his second marginalization, however, for he literally carried it with him on his back. From the age of twelve, exactly at the time of the family move from London, Pope suffered from a form of tuberculosis that affected the bone, deforming his body, stunting his growth. Pope grew to a height of only 4 feet 6 inches (1.37 m), and was left with a severe hunchback.

Drawing of a person suffering from Pott’s desease

The disease received its formal medical description in Pope’s lifetime, though too late to help the poet. A decade before Pope’s death in 1744, a Liverpool surgeon, H. Park, wrote an epistolary volume in which characteristics and (painful) treatments of the disease were described: An Account of a new method of treating diseases of the joints of the knee and elbow, in a letter to Mr. Percival Pott. (London: J. Johnson, 1733). The recipient of the “letter”, the remarkable English surgeon Sir Percivall Pott (1714–1788) was one of the founders of orthopedy, and the first scientist to demonstrate that cancer may be caused by an environmental carcinogen. He published a volume on Some few general remarks on fractures and dislocations (London: Hawes, Clarke and Collins, 1768), providing the first clinical description of extrapulmonary tuberculosis (tuberculous spondylitis), the disease with which Pope suffered, subsequently known as Pott’s disease.

I recommend a re-reading of Windsor Forest with some sense of the twice-excluded author in mind. All good poems can be read in many ways, but one of the things this re-reading proposes is the struggle of an outsider to create a re-vision of the world that contains and excludes him.

— Robert V. McNamee

Director, Electronic Enlightenment Project

© 2013 University of Oxford