Miscellany — June 2010

Introducing "topics" & a bit more volcanic chaos

Our new "topics" area

This month, we are introducing a new "topics" feature in the publicly accessible Information section of EE. This is the first step in a longer-term development that will see the creation of an entirely new approach to Electronic Enlightenment centred on thematic categories — an approach that will offer exciting new dimensions for users to engage with and contribute to EE.

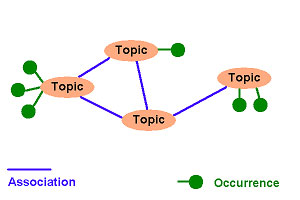

Topic map by Hirzel, Wikipedia project.

What are "topics" as currently offered in EE?

At their simplest, as presented in the public pages of Electronic Enlightenment, topics are selected group of themes such as "History" or "Society" with links to a small but interesting selection of relevant documents and people, intimating the further riches to be found in EE's complete collection.

Icelandic ash cloud still an annoyance? . . . consider 1783!

Although European airspace continues to be irregularly plagued with the ash cloud spewing from the Eyjafjallajokull crater in Iceland, complaints about the inconvenience are put into perspective by the Icelandic eruption of 1783–1784.

Laki Craters (image: Dr Claire Witham)

On 8th June 1783, some 90 km north-northeast of the current hot-spot, a volcanic fissure containing over 130 craters opened in an area called Lakagígar ("Craters of Laki"). The eruption continued for 8 months to the 7th February 1784 (a neighbouring crater, Grímsvötn, continuing to erupt until 1785). An estimated 8 million tons of hydrofluoric acid and 120 million tons of sulfur dioxide spewed into the atmosphere creating what has become known as the "Laki haze". Temperatures dropped globally. Liverstock died in their thousands and crops failed across Europe; the Asian monsoon cycle was disrupted causing droughts in India and famines from Egypt to Japan; and travelling West to East the "fog" reached round the globe to America, where that winter the Mississippi reportedly froze at New Orleans. Modern estimates put the worldwide death toll at 2 million+. Some environmental historians have even suggested that the crop failures and ensuing food poverty added fuel to dissatisfactions in France, helping trigger revolution. For a modern scientific view on the Laki eruption, see Witham, C. S. & C. Oppenheimer, "Mortality in England during the 1783–4 Laki Craters eruption", Bulletin of Volcanology (Springer: Berlin / Heidelberg, 67:1, December 2004, pp. 15–26). This is the first attempt to scientifically quantify European impacts of the 18th-century Icelandic eruption by the imaginative use of historical mortality and temperature datasets. This illustrates the potential for substantial continental health impacts of large eruptions.

18th-century scientists comment on the effects of Laki

Various reports of the strange and destructive atmospheric conditions were made at the time, and though devastating volcanic eruptions in Iceland were noted (see Franklin's letter below), it seemed more coincidence than cause of the global disaster.

1783: Rev. Sir John Cullum reports to the Royal Society

Rev. Sir John Cullum writes to the Royal Society from Hardwick Hall, outside Bury St Edmonds, to say that the "[barley] became brown and withered . . . as did the leaves of the oats; the rye had the appearance of being mildewed". Cullum further recorded that:

. . . I observed the air very much condensed in my chamber window and, upon getting up, was informed by a tenant that, finding himself cold in bed, at about three o'clock in the morning, he looked out of his window and, to his great surprise, saw the ground covered with a white frost. I was assured that two men at Barton, about three miles off, saw, in some shallow tubs, ice of the thickness of a crown-piece.

Eruption image: USGS)

May 1784: Benjamin Franklin's "Meteorological Imaginations & Conjectures"

US Ambassador to France, Benjamin Franklin, writes from his home in the XVIe arrondissement of Paris to one of his learned correspondents, Dr Thomas Percival (1740–1804, English physician and early medical researcher), reviewing the meteorological oddities of the previous year:

During several of the summer months of the year 1783, when the effects of the sun's rays to heat the earth in these northern regions should have been the greatest, there existed a constant fog over all Europe, and great part of North America. This fog was of a permanent nature ; it was dry, and the rays of the sun seemed to have little effect towards dissipating it, as they easily do a moist fog, arising from water. They were indeed rendered so faint in passing through it, that, when collected in the focus of a burning-glass, they would scarce kindle brown paper. Of course, their summer effect in heating the earth was exceedingly diminished.

Hence the surface was early frozen.

Hence the first snows remained on it unmelted, and received continual additions.

Hence perhaps the winter of 1783–4, was more severe than any that had happened for many years.

The cause of this universal fog is not yet ascertained. Whether it was adventitious to this earth, and merely a smoke proceeding from the consumption by fire of some of those great burning balls or globes which we happen to meet with in our rapid course round the sun, and which are sometimes seen to kindle and be destroyed in passing our atmosphere, and whose smoke might be attracted and retained by our earth ; or whether it was the vast quantity of smoke, long continuing to issue during the summer from Hecla, in Iceland, and that other volcano which arose out of the sea near that island, which smoke might be spread by various winds, over the northern part of the world, is yet uncertain."

— Percival communicated the letter to the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester,

who first published it as "Meteorological Imaginations and Conjectures" in the Memoirs

of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester (Vol. II. p. 357).

1789: a naturalist looks back on that "portentous" summer

In his Natural History of Selborne, published in London in 1789, Gilbert White (1720–1793, English naturalist and clergyman) describes the summer of 1783 as:

. . . an amazing and portentous one . . . the peculiar haze, or smokey fog, that prevailed for many weeks in this island, and in every part of Europe, and even beyond its limits, was a most extraordinary appearance, unlike anything known within the memory of man.

The sun, at noon, looked as blank as a clouded moon, and shed a rust-coloured ferruginous light on the ground, and floors of rooms; but was particularly lurid and blood-coloured at rising and setting. At the same time the heat was so intense that butchers' meat could hardly be eaten on the day after it was killed; and the flies swarmed so in the lanes and hedges that they rendered the horses half frantic . . . the country people began to look with a superstitious awe, at the red, louring aspect of the sun.

— The natural history and antiquities of Selborne, in the county of Southampton (London, 1789)

18th-century poetic traces & local effects

Wherever the Laki eruption is discussed, the contemporary scientific remarks are often quoted. One of the pleasures afforded by EE, however, is the discovery that the sensitivities of a poet observing the natural world could add significantly to our understanding of this odd and dangerous time. Indeed, unlike the scientific observers the poet shows an acute sense of the associated human costs in the local community.

Friday, 13 June 1783: five days into the eruption & Southern England is in a fog

Growing numbers of people and animals are already dead and dying in Iceland, when an oblivious England is overtaken by the spreading disaster. A week before the Summer solstice, the English poet William Cowper writes the first in a sequence of letters (this one to his great friend, the reformed slave-ship captain John Newton), reporting on the expanding tragedy. The letters demonstrate his acute eye for the natural world, a sensitivity that would make his poems on natural and rural themes amongst the most popular 18th-century literary works for a succeeding, romantic generation of poets.

. . . I am and always have been a great Observer of natural appearances, but I think not a superstitious one. . . . It is impossible however for an Observer of natural phænomena not to be struck with the singularity of the present season. The fogs I mention'd in my last still continue, though 'till yesterday the Earth was as dry as intense Heat could make it. The Sun continues to rise and set without his rays, and hardly shines at noon even in a cloudless sky. At Eleven last night the moon was of a dull red, she was nearly at her highest elevation and had the colour of a heated Brick. She would naturally I know have such an appearance looking through a misty atmosphere, but that such an atmosphere should obtain for so long a time and in a Country where it has not happen'd in my remembrance, even in the Winter, is rather remarkable. We have had more Thunder storms than have consisted well with the peace of the fearfull Maidens in Olney, though not so many as have happened in places at no great distance, nor so violent. Yesterday morning however at 7 o'clock, two fire balls burst either in the steeple or close to it. William Andrews saw them meet at that point, and immediately after saw such a smoke issue from the apertures in the steeple as soon render'd it invisible. I beleive no very material damage happen'd, though when Joe Green went afterward to wind the clock, flakes of stone and lumps of mortar fell about his ears in such abundance, that he desisted and fled terrified. The noise of the explosion surpassed all the noises I ever heard, you would have thought that a thousand sledge hammers were battering great stones to powder, all in the same instant. The weather is still as hot, and the air as full of vapor, as if there had been neither rain nor thunder all the summer. . . .

— EE letter id: cowpwiOU0020142a1c

Tuesday, 17 June 1783: the seasons are out of joint

Summer is still several days away, but not for our poet, writing again to Newton.

. . . The Summer is passing away, and hitherto has hardly been either seen or felt. Perpetual clouds intercept the influences of the Sun, and for the most part there is an Autumnal coldness in the weather, though we are almost upon the Eve of the longest day. We are glad to find that you still entertain the design of coming, and hope that you will bring Sunshine with you. . . .

— EE letter id: cowpwiOU0020144a1c

Sunday, 29 June 1783: superstition & drink are coming to the fore

Another to Newton: the strange "meteorological" conditions are starting to work on rural superstitions (and thirsts), though as Cowper notes, the atmospheric contamination is more likely to affect people in the clean air of the countryside than in stygian London.

. . . The Bœotian atmosphere ["The district of Bœotia in Greece, as Hesiod claimed, has a very unpleasant climate with winters which are humid and foggy."] I have breathed these six days past, makes such a Sally of Genius the more surprising. So long, in a country not subject to fogs, we have been cover'd with one of the thickest I remember. We never see the Sun but shorn of his beams, the trees are scarce discernible at a mile's distance, he sets with the face of a red hot salamander, and rises (as I learn from report) with the same complexion. Such a Phænomenon at the end of June, has occasioned much speculation among the Connoscenti at this place. Some fear to go to bed, expecting an Earthquake, some declare that he neither rises nor sets where he did, and assert with great confidence that the day of Judgment is at hand. This is probable, and I beleive it myself, but for other reasons. In the mean time I cannot discover in them, however alarmed, the symptoms even of a temporary reformation. This very Sunday morning the pitchers of ale have been carried into Silver-end as usual, the inhabitants perhaps judging that they have more than ordinary need of that cordial at such a juncture. It is however, seriously, a remarkable appearance, and the only one of the kind that at this season of the year has fallen under my notice. Signs in the heavens are predicted characters of the last times, and in the course of the last 15 years I have been a witness of many. The present obfuscation (if I may call it so) of all nature may be rank'd perhaps among the most remarkable. But possibly it may not be universal; in London at least, where a dingey atmosphere is frequent, it may be less observable. . . .

— EE letter id: cowpwiOU0020148a1c

Sunday, 7 September 1783: two months in & mortality rises

This time writing to Rev. William Unwin, Cowper raises the spectre of epidemic — though it seems to be read more as a result of poor "meteorological" conditions than actual atmospheric contamination.

. . . So long a silence needs an apology. I have been hinder'd by a three weeks' visit from our Hoxton friends, and by a Cold and a feverish complaint which are but just removed. A foggy Summer is likely to be attended with a sickly Autumn. Such multitudes are indisposed by fevers in this country, that the farmers have with difficulty gather'd in their harvest, the laborers having been almost every day carried out of the field incapable of work, and many die. . . .

— EE letter id: cowpwiOU0020156a1c

Monday, 8 September 1783: the epidemic worsens

Again to John Newton: Cowper makes the "epidemic" threat explicit. In an interesting aside, he reports a respiratory coincidence that is really a "cardinal symptom" of the poisoning.

. . . . The Epidemic begins to be more mortal as the Autumn comes on. Two men of drunken memory, Bob Freeman and Bob Kitchener have died of it, since you went, and in Bedfordshire it is reported, how truely however I cannot say, to be nearly as fatal as a plague. . . . Mr. Scott has been ill almost ever since you left us. This light atmosphere and these unremitting storms are very unfriendly to an asthmatic habit. He suffers accordingly . . . .

— EE letter id: cowpwiOU0020159a1c

Monday, 29 September 1783: a final letter in our sequence, to Rev. Unwin

Summer has passed, the air is clearer, the sun brighter. A hard, hard winter lies ahead and thousands upon thousands will die — for as we know from Eyjafjallajoekull, not being able to see the cloud doesn't mean it isn't there. But atmospheric improvement in Bedfordshire leads Cowper to round-out our look at responses to the Laki haze. The poet considers the "wisdom" of the natural philosopher and his happy cycle of truths.

My dear William — We are sorry that you and your houshold partake so largely of the ill effects of this unhealthy season. You are happy however in having hitherto escaped the Epidemic fever which has prevailed much in this part of the Kingdom, and carried many off. Your Mother and I are well after more than a fortnight's Indisposition, which slight appellation is quite adequate to the description of all I suffer'd. I am at length restored by a grain or two of Emetic Tartar. It is a tax I generally pay in Autumn. By this time I hope, a purer æther than we have seen for Months, and these brighter Suns than the Summer had to boast, have cheered your Spirits, and made your Existence more comfortable. We are Rational, but we are Animal too, and therefore subject to the influences of the Weather. The Cattle in the fields show evident symptoms of lassitude and disgust in an unpleasant Season, and we their Lords and Masters are constrained to sympathize with them. The only difference between us is, that they know not the cause of their dejection, and we do; but for our humiliation, are equally at a loss to cure it. Upon this account I have sometimes wished myself a Philosopher. How happy in comparison with myself, does the sagacious Investigator of Nature seem, whose Fancy is ever employed in the Invention of Hypotheses, and his Reason in the support of them. While he is accounting for the Origin of the Winds he has no leisure to attend to their Influence upon himself, and while he considers what the Sun is made of, forgets that he has not shone for a Month. One project indeed supplants another, the Vortices of Descartes gave way to the Gravitation of Newton, and this again is threat'ned by the Electrical fluid of a modern. One Generation blows Bubbles, and the next breaks them. But in the mean time your Philosopher is a happy Man. . . .

— EE letter id: cowpwiOU0020164a1c

— Robert V. McNamee

Director, Electronic Enlightenment Project

© 2010 University of Oxford