Friday Coffee Gathering — August 2023

Jack Orchard <jack.orchard@bodleian.ox.ac.uk>

Content Editor for Electronic Enlightenment

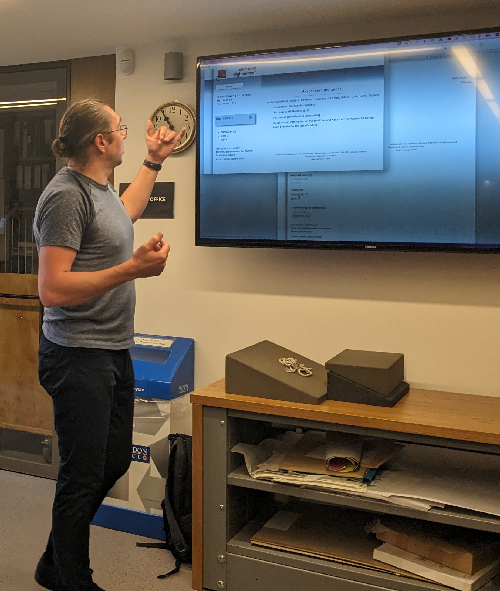

On 18 August 2023, Electronic Enlightenment delivered a short presentation in the Bodleian Libraries’ Friday Coffee Gathering series in the Weston Library Visiting Scholar’s Centre, organised by Alexandra Franklin, Co-ordinator of the Centre for the History of the Book, and Chris Fletcher, Keeper of Special Collections at the Bodleian. This event series, which takes place every Friday at 10.30, combines an informal networking session for Bodleian staff and visiting scholars with a showcase of significant items or recent acquisitions from the Bodleian special collections. Recent sessions have included Dr Robert Spindler showcasing early modern broadside ballads, Bodleian Map Curator Dr Martin Davis on Soviet-Era maps of Oxford, and Dr Thandeka Cochrane (King’s College London) on medical records from colonial Africa (1940-1960). For Electronic Enlightenment’s session, Technical Editor Mark Rogerson and myself showcased a selection of some of the circa 3,500 letters which are both published in scholarly edited format by us, but which have their original manuscripts in the Bodleian collections, and reflected on the editorial histories which brought these letters to their current digital format, as well as the value for us as a project in being able to return to the source texts in our own home institution.

Mark Rogerson, Technical Editor

Jack Orchard, Content Editor

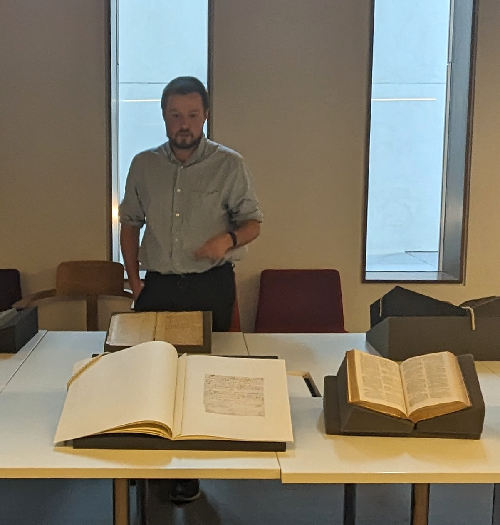

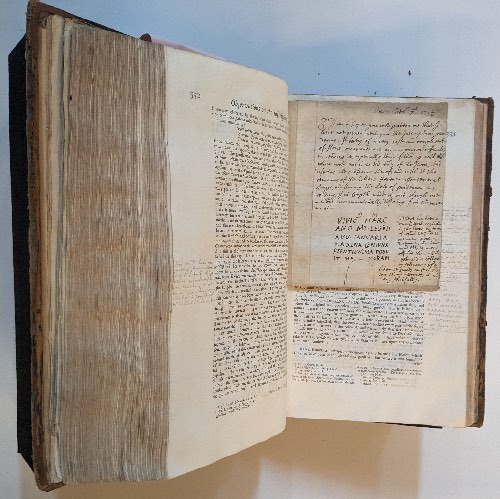

The first letter we discussed was Edward Young to Samuel Richardson, 26 January 1755, a brief letter discussing the poet Edward Young’s forthcoming publication, The Centaur not Fabulous (1755), a satirical essay on contemporary vice and licentiousness which is structured as a series of letters addressed to novelist, printer, and taste-maker Samuel Richardson. Richardson’s editorial guidance and contribution to the writing of Centaur was so significant that Bluestocking scholar Hilary Havens has recently argued that he can be better described as co-author of the work, rather than just it’s recipient. This letter gives us a snapshot of this creative collaboration in action. but also represents an interesting case study in transmission history. We were able to not only display the original manuscript letter, with Young’s signature, which can be found at MS. Montagu d.18 in the Bodleian Archive, but also the first printed edition of this letter in the April 1816 issue of the London periodical, the Monthly Magazine, alongside the critical edition of the letter in the 1971 edition of Young’s letters by Henry Pettit.

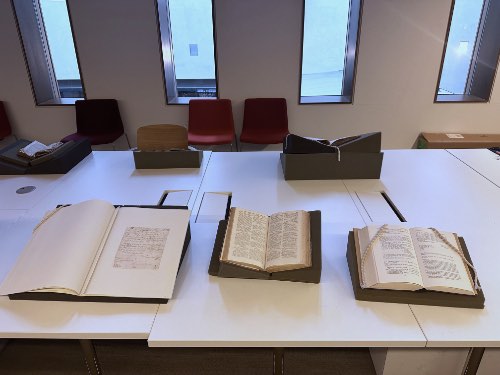

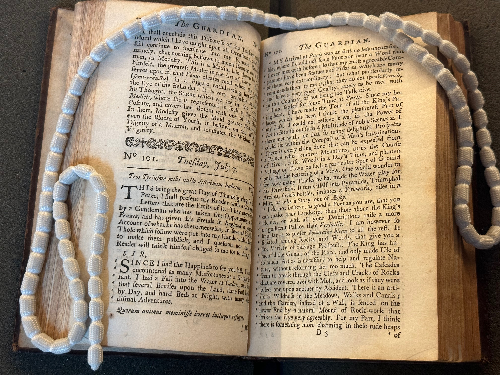

Left to right: MS Montagu d. 18; Monthly Magazine, April 1816; The correspondence of Edward Young, 1683-1765, edited by Henry Pettit

We also displayed both the Tickell Letter Book (Dep. D.10) and a copy of the second volume of a 1740 compilation of The Guardian magazine, which had its original run in 1713. The Tickell Letter book is a collection of letters written from Joseph Addison to a range of different correspondents, including politician Charles Montagu and diplomat Henry Newton. What is most interesting from our perspective is not necessarily Addison’s correspondents themsleves, however, but the fact that passages from several of these letters, such as Joseph Addison to William Congreve, August 1699 and Joseph Addison to Reverend John Hough, bishop of Worcester, 15 October 1699, were edited by Addison himself, alongside his collaborator Richard Steele to become part of the epistolary essays which formed The Guardian’s content. In the Tickell Book itself, the reader can see where Addison or Steele marked the original letters to excerpt discussions of the former’s visit to France, which would be augmented, re-structured, and re-ordered to become the travel-writing sections of Guardian Issue 101.

Bodleian Libraries Special Collections Dep. D.10, Tickell Letter book

Bodleian Libraries Vet. A4 f.620, The Guardian magazine volume 2

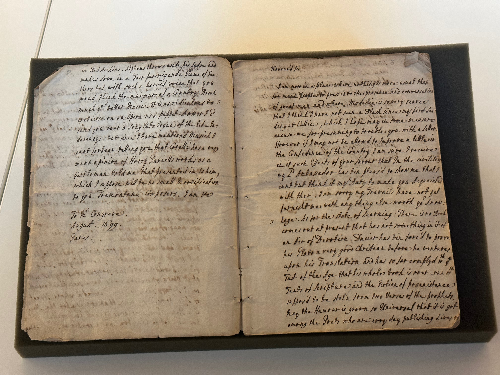

We also displayed a collection of letters by and about the poet Alexander Pope, which can be found in the Bodleian under MS. Rawl. 90 H (Letters) - in which we focused on the letter described in S. E. to Edmund Curll, 3 September 1735. As George Sherburn, editor of the 1956 edition of Pope’s letters which forms Electronic Enlightenment’s base text, notes, this letter was appended to a set of spurious letters purported to be between Pope himself and Martha Blount, which the poet’s unscrupulous editor, Edmund Curll, was attempting to publish. The likelihood is that this letter, and the pseudonym of S.E, was fabricated by Curll himself, and for this reason, the text of this letter was not published in full in Sherburn’s edition - Electronic Enlightenment is in the position, however, to publish the text alongside Sherburn’s explanation of its provenance. Where Sherburn’s focus was on establishing a canon of Pope’s correspondence in his edition, Electronic Enlightenment is invested in the transmission of historical letters regardless of authorship or status, and this document, alongside the false letters it accompanied, represents a fascinating piece of Edmund Curll’s epistolary history, even if they are not connected to the celebrated poet.

Bodleian Libraries Special Collections MS. Rawl. letters 90

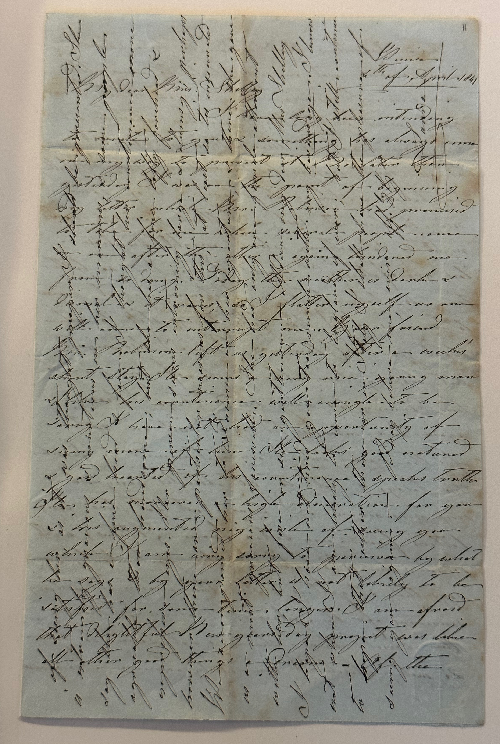

At the opposite end of the eighteenth-century from Pope and Addison we find one of the collections which Electronic Enlightenment has already made available in digital facsimile, the letters of Laura Galloni d’Istria and her circle, which included Mary Shelley and Clara Clairmont. Beyond their content, which offers a fascinating glimpse into the social and cultural life of Mary Shelley’s circle in Italy in the 1840s, these letters are notable for the fact that both d’Istria and Clairmont practiced ‘cross-writing’ — making the fullest use of the avialable space on the page by continuing their letter vertically, once all the sides of the paper had been written on horizontally. This practice, which required an extremely neat hand, was practiced by d’Istria on very small sheets of paper, making the elegance of the technique even more striking.

Bodleian Libraries Special Collections MS. Abinger c. 50

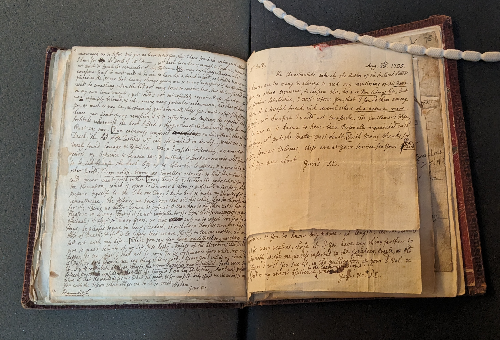

Like Galloni D’Istria’s beautiful cross-written letters, the handwriting of James Weldon, ammanuensis to philosopher Thomas Hobbes is worth examination on its own merits. This elegant hand in which he not only wrote the original manuscript of Hobbes’ political treatise Behemoth (1668) but also Thomas Hobbes to John Aubrey, 4 April 1679, the letter we chose to display, is highly recognisable alongside the other items of correspondence to be found in MS. Aubrey 9. This collection compiles the materials which John Aubrey used in composing his famous collection of short biographies, the Brief Lives. What is notable in relation to this specific letter, which forms part of Aubrey’s biography of Hobbes in the Lives, is that it actually appears twice in the same collection, first in the aforementioned hand of James Weldon, and later in Aubrey’s own, far more workmanlike, handwriting, as part of the early draft manuscript of his complete work. The version of the text in Electronic Enlightenment is a hybrid document which includes textual variants from both versions of the letter.

Bodleian Libraries Special Collections MS. Aubrey 9

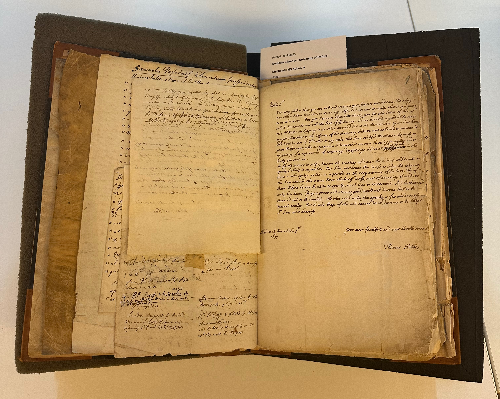

The phenomenon of compiling the correspondence used to compose a work of collaborative scholarship was not limited to Aubrey, as attested by the final document we displayed, a majestic large format copy of the Britannia Romana (1732) by antiquarian John Horsley (1685-1732), which can be found through the Bodleian’s SOLO catalogue, under Gough Gen. top. 128. This book, which documents the known roman ruins and artefacts across Britain in the early 18th century, complete with copperplate illustrations and a descriptive geographical breakdown of the country, reflects the practice known as ‘extra illustration’, when a printed book is rebound, with additional material not in the original printing incorporated between the covers. In this case, the body of collective antiquarian knowledge on which Horsley based the book, in the form of letters, sketches, and illustrations from other printed works, has been appended to the printed text - the majority at the front, but with occasional insertions throughout. It is one of these insertions which has been published in Electronic Enlightenment. Between pages 330 and 331, which describe a series of Latin inscriptions found in Middlesex and Essex, the binder of the book has inserted Edmond Halley to Roger Gale, 18 February 1709. This letter, which predates Horsley’s work by 20 years, is addressed to Roger Gale, another antiquarian, who wrote in 1709, and provides a description of a Latin inscription which Horsley also reproduces several pages earlier in Romana Britannia. The fact that this letter was bound into Horsley’s work, identifying Halley as the source of this information, even while the text reproduces the illustration from Gale’s 1709 work, the Antonini Iter Britanniarum (1709) highlights the value of this book as a testament to the collaborative nature of antiquarian scholarship across the eighteenth-century, and would be a fascinating resource for people interested in scholarly networks and collaboration, to explore further. The letter is notable in Electronic Enlightenment not only for the light it shines on Halley outside of his scientific interests, but also for the fact that we have reproduced the sketch Halley made of the inscription.

Bodleian Libraries Gough Gen. top. 128

We are looking for users of Electronic Enlightenment to write posts for our blog on how Electronic Enlightenment fits into their research - please contact me on jack.orchard@bodleian.ox.ac.uk if you are interested.